Published in InPractice, Spring 2021: Volume 15, Issue 2

Sahar N. Saleem

Department of Radiology

Kasr Al Ainy Faculty of Medicine

Cairo University Egypt

Zahi Hawass

Former Minister of Antiquities of Egypt, Cairo

Ancient Egyptians believed in an afterlife, that it was necessary to preserve the body after death. They perfected the process of mummifying the dead and buried them with their treasures in deep underground burial shafts, as in the Saqqara necropolis, or in expertly crafted mountain tombs, such as The Valley of Kings.

Paleoradiology: Imaging the Insides

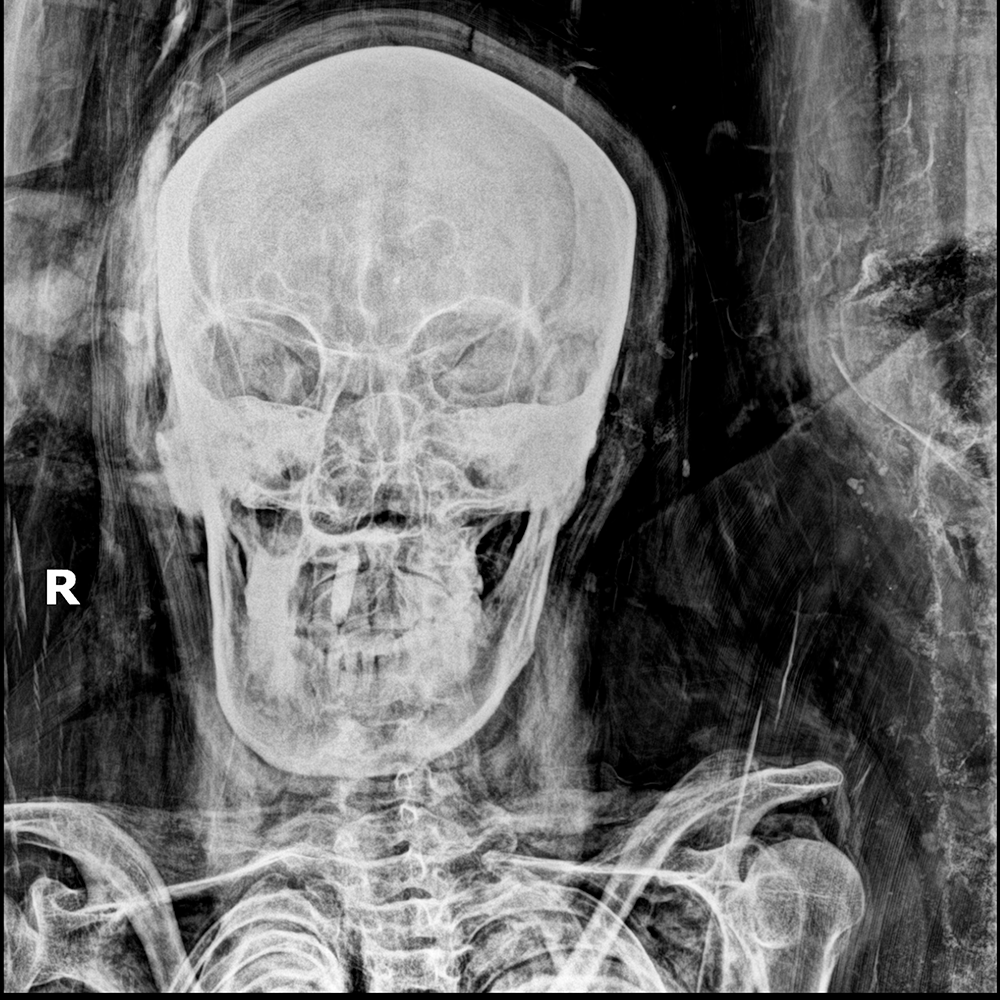

In 1896, only a few months after the discovery of radiography, prior to its use on living humans, the first tests of the mysterious form of radiation were done on Egyptian mummies: one of a human and one of a cat. For the first time, x-ray film showed what was inside a mummy—without the need to dissect or even unwrap it. This event marked the birth of paleoradiology. The term refers to the use of non-invasive medical imaging modalities to study ancient human and animal remains or objects. Paleoradiology has evolved alongside medical imaging methods since its first uses. Today, a wide array of imaging modalities can be applied in archaeological work: conventional radiography, computed radiography, direct digital radiography, CT, micro-CT, endoscope, and MRI.

Latest Findings in Saqqara

The Saqqara necropolis had been an ancient burial site since the Old Kingdom (ca. 2686–2181 B.C.) and was in use through much later periods for royalty, noblemen, priests, and even common people. Located about 30 kilometers south of present-day Cairo, Saqqara is a United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site, hosting several archaeological excavations. Our recent mission at Saqqara, near the pyramid of King Teti (2323–2291 B.C.), unearthed great discoveries, including the temple of Queen Naeret, wife of King Teti. We also discovered 52 burial shafts (1522–1069 B.C.), containing coffi ns and a large number of rare artifacts: statues, board games, jewelry, amulets, stellas, as well as a papyrus 3 meters long by 1 meter wide with inscriptions from The Book of the Dead.

Field Paleoradiology: Imaging With Archaeological Context

Paleoradiology can give us important information regarding the condition of a mummy or other ancient artifacts. Imaging mummies in a proper facility provides the optimum technical conditions. However, during excavations, it is often impractical to transport mummies to an imaging facility; it may even be harmful to vulnerable mummies. Instead, we use dedicated mobile imaging equipment to reach the mummies inside their tombs, a nondestructive option by which we can accomplish the same goals.

Traditional radiography has been used in field paleoradiology, but it is a cumbersome process to develop x-ray film in situ. Therefore, we use computed radiography and direct digital radiography technologies that have the advantage of being filmless systems, allowing for instant review and further manipulation of displayed images.

Conquering Technical Challenges

Careful site inspection is crucial preparation for the use of these field paleoradiology techniques. First, we determined the topography of the site—type, position, and relationship of the burial objects—and the data we intended to collect. We then identified any safety concerns, like applying radiation protection measures to conduct responsible field paleoradiology. The burial shaft in Saqqara was narrow, located 10 meters underground, leading to a room jammed with more than 50 coffins stacked atop one other. To better navigate this architecture, we designed detachable, lightweight radiography accessories that we could bring down and mount inside the burial shaft. These included a tube holder, a framed mummy bed with a plexiglass top, as well as a cassette holder for lateral viewing.

We x-rayed the closed coffins, altering radiographic exposure settings and positioning according to the mummification style and the structures we aimed to visualize: bony skeletons, dense amulets, or soft tissues.

Interpretation Issues

Unlike patients, mummified remains do not have clinical history, and their historical context is often questionable. In fact, we identified a female mummy via radiograph that had been placed inside a coffin bearing inscriptions of a male’s name. The interpretation of mummy radiography also requires awareness of the ways in which the desiccation of human tissue affects its morphology, as well as the changes that resulted from different mummification practices. Additionally, some mummified bodies could be covered by artifacts that might be misinterpreted as pathology.

Thus far, our field paleoradiology study has been successful, resulting in valuable details regarding the sex, age at death, and possible cause of death for the mummies in the Saqqara burial shaft. We were also able to identify jewelry, amulets, and embalming materials inside many of the mummies that reflected their socioeconomic status. Moreover, we gained new perspectives in to the health status and diseases of the studied mummies, which can provide a better understanding of the natural history of disease, itself.

Field paleoradiology allowed us to determine the mummies’ levels of preservation—to avoid moving vulnerable mummies unnecessarily. This enabled us to carry out a type of triage; mummies whose images suggested were in good condition and needed further investigations could be moved to a nearby medical facility for a CT scan, while those in more delicate condition were left in situ.

An invaluable tool to unlock the mysteries of mummification, paleoradiology puts us face-to-face with the men and women of ancient Egypt. Even thousands of years after their deaths, we’re still gaining remarkable insights into their lives simply from imaging their remains. Our work at the excavation site at Saqqara has not ended, of course, as what we have unearthed to date is merely a fraction of what we expect to exist.

The opinions expressed in InPractice magazine are those of the author(s); they do not necessarily reflect the viewpoint or position of the editors, reviewers, or publisher.