Published August 10, 2020

Alexandra M. Foust

Department of Radiology

Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School

Ricardo Restrepo

Department of Radiology

Nicklaus Children’s Hospital, Florida International University

Edward Y. Lee

Department of Radiology

Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School

Since the publication of our initial AJR article, “Pediatric SARS, H1N1, MERS, EVALI, and Now Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pneumonia: What Radiologists Need to Know”, the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has continued to grow—more than 15.7 million cases and 640,000 deaths worldwide, as of July 26, 2020. During this time, understanding of the imaging manifestations related to pediatric COVID-19 pneumonia, and the more newly defined COVID-19-related entity multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), has continued to increase; however, substantial uncertainty regarding the imaging findings of pediatric COVID-19 and MIS-C still exist. Our article highlights a few key points regarding what is currently known about the imaging findings of pediatric COVID-19 and MIS-C for practicing radiologists.

What is Typical Pediatric COVID-19?

A recent meta-analysis of 7,780 pediatric patients positive for COVID-19 found that the mean age of patients was 8.9 years with a slight male predominance (55.6%). Underlying comorbid medical conditions were identified in 35.6% of patients. Overall, pediatric patients demonstrated a more mild clinical course than adults with 19.3% of patients completely asymptomatic, 3.3% requiring intensive care, and only 7 reported deaths (0.09%). The most commonly observed clinical complaints among symptomatic patients were cough and fever, and elevated inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, and interleukin-6 were frequent.

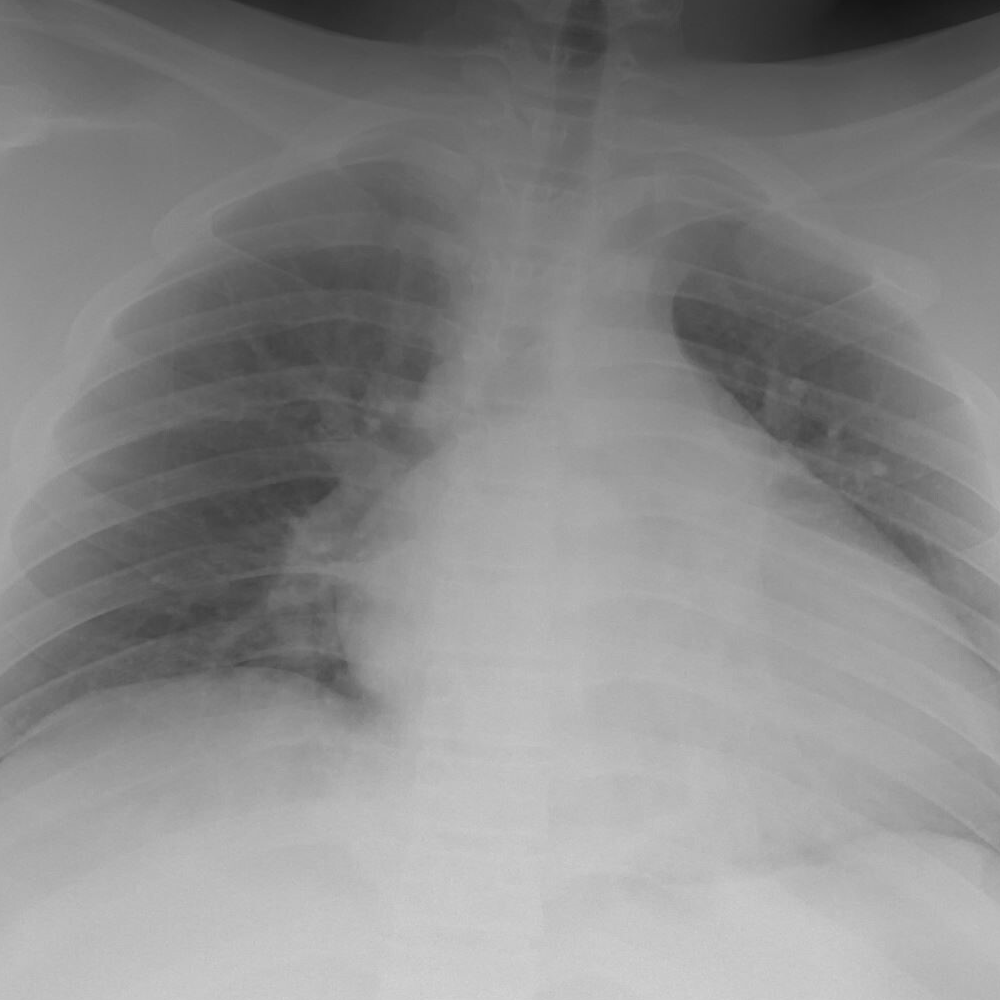

Radiographically, typical imaging findings of pediatric COVID-19 pneumonia have been characterized as bilateral peripheral and/or subpleural ground-glass opacities and/or consolidation in a lower-lobe predominant distribution.

Although a unilateral or bilateral distribution of parenchymal abnormality may be observed in pediatric COVID-19 pneumonia, the differential for unilateral disease is somewhat broader. Thus, a unilateral distribution has been defined as indeterminant. The halo sign, a rounded consolidation surrounded by a rim of ground-glass opacity, can be seen during the early phase of pediatric COVID-19. Therefore, the halo sign is also considered typical when present in an immunocompetent patient, as it has a narrow differential. Additional important considerations for radiologists are atypical imaging findings that raise concern for alternative diagnosis, including centrilobular nodules, focal segmental/lobar consolidation, cavitary lesions, pleural effusion, and lymphadenopathy.

What is Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C)?

As suggested by the name, MIS-C is a post-viral inflammatory syndrome observed in pediatric patients with prior COVID-19 infection (within the past 4 weeks) that results in injury to multiple organ systems, most frequently involving > 4 systems. Some researchers have called MIS-C a “Kawasaki-like” disease due to the potential overlap in clinical presentation, including fever, conjunctivitis/rash, cardiac dysfunction + coronary artery dilation, and hemodynamic instability. Unlike pediatric COVID-19 pneumonia, children who develop MIS-C demonstrate a more severe clinical course, requiring intensive care management in up to 85% of cases, and have a higher death rate of 4%. As might be expected, the imaging findings in MIS-C differ from those observed in typical pediatric COVID-19 pneumonia.

What Are Important Differences Between Typical Pediatric COVID-19 and MIS-C?

Thoracic Findings

Chest imaging studies in pediatric patients with MIS-C may be normal or may demonstrate abnormalities, mainly related to underlying cardiac dysfunction. On chest radiograph, this may manifest as cardiomegaly, increased prominence of pulmonary vasculature, interstitial edema, or pleural effusions.

Chest CT may show similar findings and, in some cases, may demonstrate pericardial effusions, coronary artery dilation, and/or pulmonary embolism. Echocardiograms often demonstrate left ventricular dysfunction and/or reduced ejection fraction, as well as pericardial effusion, and/or coronary artery dilation.

Whereas typical COVID-19 pneumonia presents with bilateral peripheral and lower-lobe predominant ground-glass opacities and consolidation, the distribution of pulmonary parenchymal abnormality in MIS-C tends to be central and perihilar in distribution and more frequently presents as increased pulmonary vascularity, although airspace consolidation may be seen in advanced stages of cardiac failure. Additionally, cardiomegaly and pleural/pericardial effusions are often observed in MIS-C, but they are rare in pediatric COVID-19 pneumonia.

Extra-thoracic Findings

Extra-thoracic manifestations are not generally observed in pediatric COVID-19 pneumonia. However, as may be expected in an inflammatory disorder involving multiple organ systems, extra-thoracic findings are not uncommon in MIS-C—especially in the abdomen. Reported intra-abdominal abnormalities in MIS-C include bowel wall thickening, ascites, right lower quadrant fat stranding and/or lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly, gallbladder sludge and/or pericholicystic fluid, and increased renal cortical echogenicity.

Five Take-Home Points for Diagnostic Radiologists

- “Typical” pediatric COVID-19 pneumonia presents as bilateral peripheral and lower-lobe predominant ground-glass opacities/consolidation + halo sign.

- Centrilobular nodules, parenchymal cavitation, focal lobar/segmental consolidation, pleural effusion, and lymphadenopathy are atypical in pediatric COVID-19 pneumonia.

- MIS-C has a more severe clinical course than pediatric COVID-19 pneumonia, often involving > 4 organ systems, with up to 85% of patients requiring intensive care.

- Thoracic imaging findings observed in MIS-C, including cardiomegaly, pleural/pericardial effusion, coronary artery dilation, or pulmonary embolism, differ from typical findings in pediatric COVID-19 pneumonia.

- Extra-thoracic manifestations are not uncommon in MIS-C and generally are a manifestation of inflammatory change (bowel wall thickening, lymphadenopathy, fat stranding, pericholicystic fluid, ascites) and/or organ dysfunction (hepatomegaly, increased renal cortical echogenicity).

As our understanding of pediatric COVID-19-related disease continues to grow, it is essential for practicing radiologists to be aware of the imaging findings in this patient population. Additionally, as the imaging features are quite different, awareness of the differences between pediatric COVID-19 pneumonia and MIS-C are critical to accurate diagnosis and optimal management of pediatric patients.

The opinions expressed in InPractice magazine are those of the author(s); they do not necessarily reflect the viewpoint or position of the editors, reviewers, or publisher.